The Try to Praise the Mutilated World project comes to an end today, as does the second English lockdown. If you have enjoyed these prompts and want to pay it forward, please give something to the Trussell Trust who help to look after our food banks and people in the most urgent need, in these desperate times. You can make a donation here. Every little helps.

When this project began one month ago, I promised you an imaginary community with real poets. We built one, raising over £150 for the Trussell Trust in the process. I also promised that you would come out of lockdown with a sheaf of new poems. If that hasn’t happened, be kind to yourself. They will come when they are ready.

Now – it’s the first day post-lockdown in England, and for many of us that won’t make a whole lot of difference. So give yourself a day off from the end of the world. Turn off the damn news and completely relax into today’s theme – which is comfort and joy. You can’t put the pandemic right out of your mind, of course; but today we revel, wholly and immersively, in whatever brings comfort and/or real joy. To get into the proper frame of mind, have a listen to our Spotify playlist, an eighteen-hour mix tape of happy, uplifting or peaceful sounds.

Start with what gives you deep, physical comfort at the moment. Given the circumstances, it’s likely to be private and simple: a hot water bottle, a hot bath, a blast down a hill on a mountain bike, a backyard bonfire with the kids, a book with a happy ending. If your comforts are specific to lockdown, tell me what they are – the city sky uninterrupted by air traffic, the illicit pleasure of having no meetings to dress up for; lazy lie-ins with your partner instead of getting up for work; a towpath walk instead of a daily train journey. These physical comforts remind us that every day won from such darkness is a celebration.

That poem also brings us to another sort of comfort, which is perhaps closer to consolation – the things you tell yourself or others, to make us all feel better. Why not vividly imagine that summer trip you cancelled in 2020, and congratulate yourself on avoiding all its inconveniences? How about planning a future summer, inviting your best mate on a road trip where you will stop at every dive bar and raucous festival on the way? Will you set off fireworks, learn the accordion, wrestle the first person you see to the ground and shag them senseless? Be unrestrained and a little manic in your schemes. Or have you recalibrated your ambitions – are you a lifelong convert to quieter pleasures?

Even in the very darkest times there are curious moments of joy, whose brightness is remarkable precisely because of the black background. Don’t think too hard about what offers comfort or joy; the simplest episode can be enough. In a more general way, think about what has given you joy in normal, pre-pandemical life. Rock climbing, raves, a concert with 1,000 people, a football match with 30,000; a Parkrun, a bikers’ rally, a weekend stay with friends. Any instance that gave you real, deep happiness, and stayed with you. Inhabit it. Remember what it smelled like. Take us there, for no other purpose than to relive it. Explain these past pleasures to a toddler or a teddy bear; retell that hilarious incident when your mate fell into the toilet at Glastonbury and you all laughed till it hurt; relive that wedding or bat mitzvah where the joys of family were best shown in small gestures. Let joy kill you, and keep away from the little deaths.

You don’t have to add ‘and I wonder if we will ever do that again?’ at the end. In fact, when you’ve finished your first draft, have a look at your fresh and twitching poem – with a cleaver in one hand. Best-selling pulp novelist Elmore Leonard famously advised, ‘Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.’ Leave out the boring bits, in other words. The single thing poets hear most in any workshop (especially mine) is, ‘Can you lose the last two lines?’ The very end of the poem is where we usually explain, once again. everything that the poem has already said – just to be sure that the stupid reader is getting it. The reader is not stupid. The reader is you.

This year has been hard. If you feel bad about feeling bad, then take your comfort from the advice that tortured soul Gerard Manley Hopkins gave to himself; My own heart let me have more pity on. If, like me, you find Hopkins’ syntax unforgiving, hear me reading it here. You can also visit the Poetry Foundation, whose site I have mined so thoroughly in writing these prompts. Start with their fine collection of Poems of Hope and Resilience. But for today’s prompt, we follow Robert Frost’s advice for the poet: ‘Begin in delight, and end in wisdom’. I can’t promise the wisdom – but do, please, unfold into the delight. It will do you a power of good.

Thank you for travelling with me through lockdown. It has been both a comfort and a joy to see so many poets carving something beautiful out of this monolithic lockdown. The work you have written has taken my breath away every single day of this curious month, and it will start to speckle the poetry journals in months to come. Stay safe, keep writing, keep paying attention.

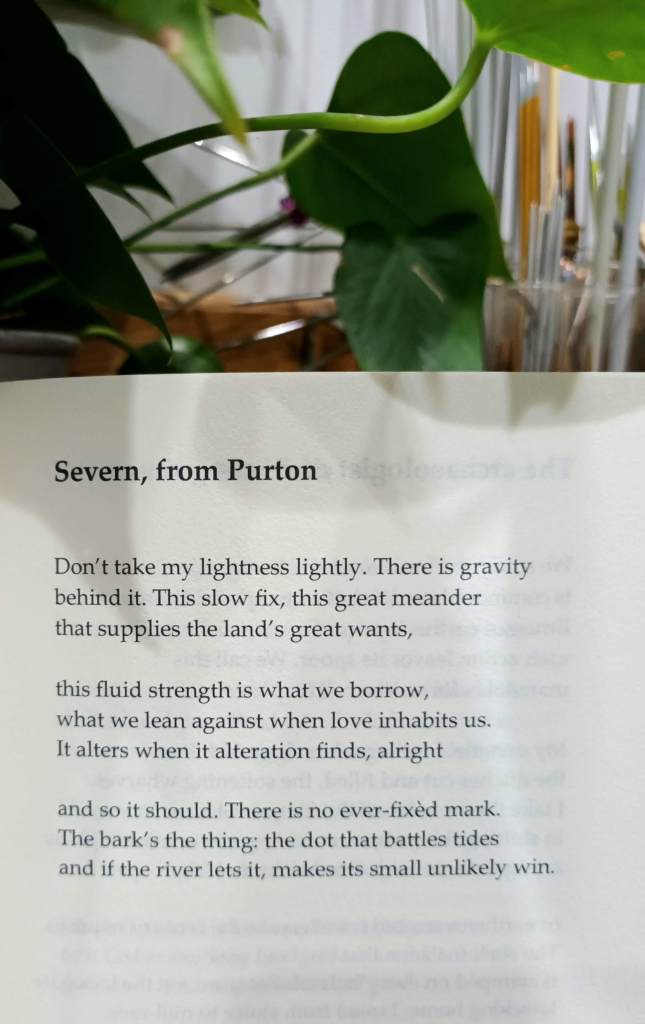

I will see you here on Christmas Day, for one final prompt to keep us writing together. Meanwhile, share one of my own private joys here 🙂